Careful management of this essential global resource is a key feature of a sustainable future. However, at the current time, there is a continuous deterioration of coastal waters owing to pollution, and ocean acidification is having an adversarial effect on the functioning of ecosystems and biodiversity. This is also negatively impacting small scale fisheries.

Saving our ocean must remain a priority. Marine biodiversity is critical to the health of people and our planet. Marine protected areas need to be effectively managed and well-resourced and regulations need to be put in place to reduce overfishing, marine pollution and ocean acidification.

A few facts and figures:

- Oceans cover three quarters of the Earth’s surface, contain 97 per cent of the Earth’s water, and represent 99 per cent of the living space on the planet by volume.

Climate change

- Oceans absorb about 30 per cent of carbon dioxide produced by humans, buffering the impacts of global warming.

- Carbon emissions from human activities are causing ocean warming, acidification and oxygen loss.

- The ocean has also absorbed more than 90per cent of the excess heat in the climate system.

- Ocean heat is at record levels, causing widespread marine heatwaves.

Ocean and people

- Over three billion people depend on marine and coastal biodiversity for their livelihoods.

- Globally, the market value of marine and coastal resources and industries is estimated at $3 trillion per year or about 5 per cent of global GDP.

- Marine fisheries directly or indirectly employ over 200 million people.

- Coastal waters are deteriorating due to pollution and eutrophication. Without concerted efforts, coastal eutrophication is expected to increase in 20 percent of large marine ecosystems by 2050.

- Roughly 80per cent of marine and coastal pollution originates on land – including agricultural run-off, pesticides, plastics and untreated sewage.

- Around the world, one million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute, while up to 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are used worldwide every year

- Around 680 million people live in low-lying coastal zones – that is expected to increase to a billion by 2050.

- Sustainable and climate-resilient transport, including maritime transport, is key to sustainable development. Around 80 per cent of the volume of international trade in goods is carried by sea, and the percentage is even higher for most developing countries

14.1 By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution

14.2 By 2020, sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems to avoid significant adverse impacts, including by strengthening their resilience, and take action for their restoration in order to achieve healthy and productive oceans

14.3 Minimize and address the impacts of ocean acidification, including through enhanced scientific cooperation at all levels

14.4 By 2020, effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans, in order to restore fish stocks in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield as determined by their biological characteristics

14.5 By 2020, conserve at least 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, consistent with national and international law and based on the best available scientific information

14.6 By 2020, prohibit certain forms of fisheries subsidies which contribute to overcapacity and overfishing, eliminate subsidies that contribute to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and refrain from introducing new such subsidies, recognizing that appropriate and effective special and differential treatment for developing and least developed countries should be an integral part of the World Trade Organization fisheries subsidies negotiation

14.7 By 2030, increase the economic benefits to Small Island developing States and least developed countries from the sustainable use of marine resources, including through sustainable management of fisheries, aquaculture and tourism

14.A Increase scientific knowledge, develop research capacity and transfer marine technology, taking into account the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Criteria and Guidelines on the Transfer of Marine Technology, in order to improve ocean health and to enhance the contribution of marine biodiversity to the development of developing countries, in particular small island developing States and least developed countries

14.B Provide access for small-scale artisanal fishers to marine resources and markets

14.C Enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources by implementing international law as reflected in UNCLOS, which provides the legal framework for the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources, as recalled in paragraph 158 of The Future We Want

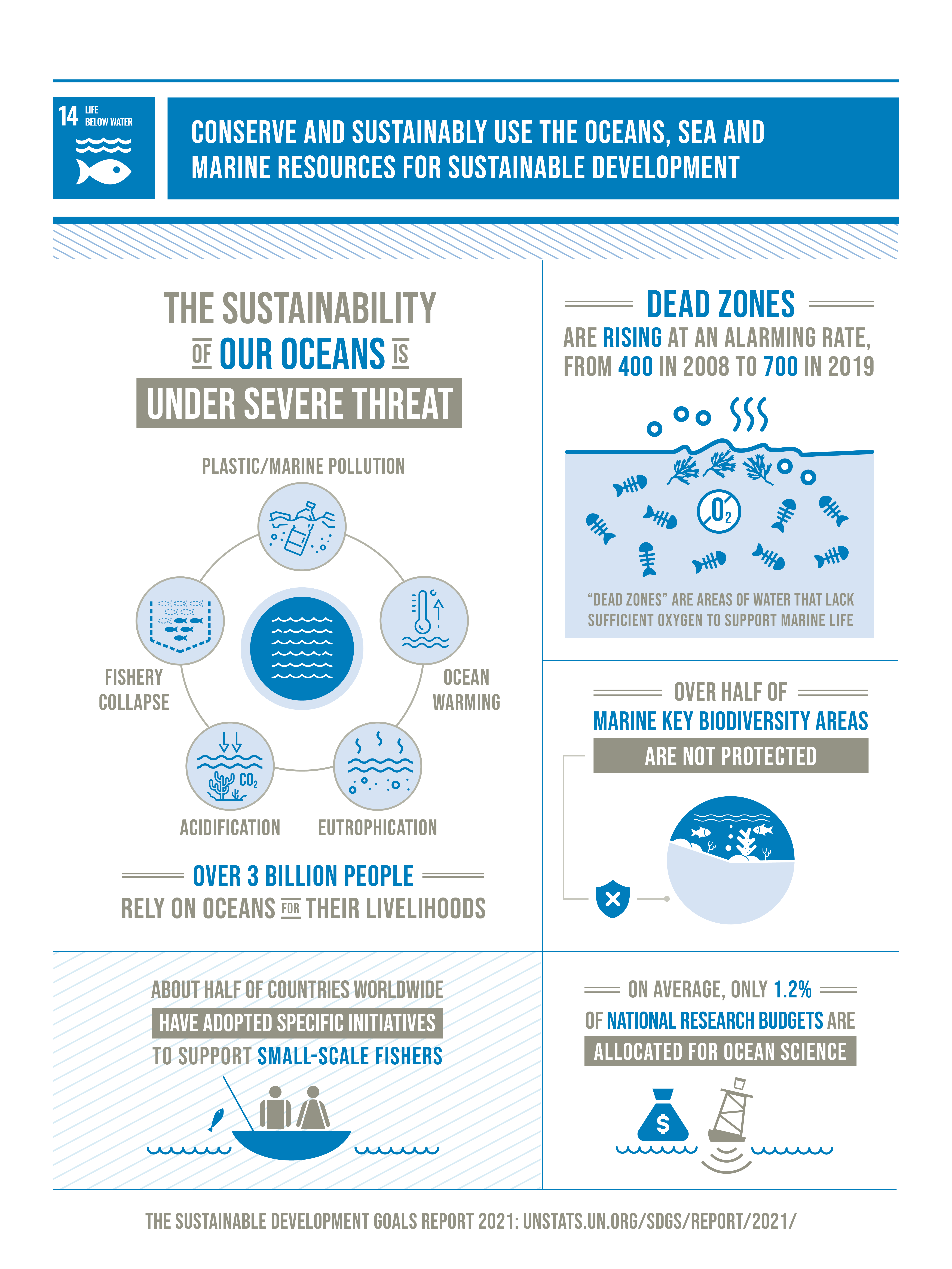

More than 3 billion people rely on the oceans for their livelihoods, and more than 80 per cent of world merchandise trade by volume is carried by sea. The oceans, seas and marine resources are under constant threat from pollution, warming and acidification that are disrupting marine ecosystems and the communities they support. These changes have long-term repercussions that require the world to urgently scale up the protection of marine environments, investment in ocean science, support for small-scale fishery communities, and the sustainable management of the oceans.

While efforts to reduce nutrient inputs into coastal zones are showing success in some regions, algal blooms indicate that coastal eutrophication continues to be a challenge. Globally, anomalies of chlorophyll-a (the pigment responsible for photosynthesis in all plants and algae) in national exclusive economic zones decreased by 20 per cent from 2018 to 2020.

Ocean acidification is caused by the absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide by the ocean, resulting in a decreasing pH and threatening marine organisms and ocean-based services. A limited set of long-term observation sites in the open ocean have observed a continuous decline in pH over the past 20 to 30 years.

Mean protected area coverage of marine key biodiversity areas increased globally from 28 per cent in 2000 to 44 per cent in 2020. However, there is considerable geographical variation in this progress, with coverage still less than one quarter of key biodiversity areas in Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand).

Improved regulation, together with effective monitoring and surveillance, has proved successful in restoring overfished stocks to biologically sustainable levels. However, the adoption of such measures has generally been slow, in many developing countries in particular. In 13 countries and territories that have active assessment and management systems in place, the proportion of fish stocks within biologically sustainable levels is higher than the world average of 65.8 per cent, according to data collected in 2019.

Between 2018 and 2020, the average degree of implementation of international instruments to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing improved around the world, with the global score measuring the implementation of the five principal instruments rising from 3 to 4 out of 5. Almost 75 per cent of States scored highly in their degree of implementation in 2020, compared to 70 per cent percent of States in 2018.

Between 2018 and 2020, the world made progress in implementing regulatory and institutional frameworks that recognize and protect access rights for small-scale fisheries, with the global score rising from 3 to 4. At the regional level, Northern Africa and Western Asia made this progress, while the regional score for Central and Southern Asia fell from 3 to 2, highlighting the need for efforts there to be redoubled and demonstrating that there is no room for complacency.

Sustainable fisheries accounted for approximately 0.1 per cent of global GDP in 2017, while contributing more than 0.5 per cent of GDP in certain regions and the least developed countries. The sustainable management of fish stocks remains critical to ensuring that fisheries continue to generate economic growth and support equitable development. The long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fisheries poses significant challenges that threaten to undermine sustainable stock management and profitability.

On average, only 1.2 per cent of national research budgets was allocated to ocean science between 2013 and 2017, with amounts ranging from 0.02 per cent to 9.5 per cent. This is a small proportion in view of the conservatively estimated $1.5 trillion contribution of the ocean to the global economy in 2010.

Many States have ratified or acceded to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (168 parties) and its implementing agreements (150 parties for the Agreement relating to the implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and 91 parties for the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement). A number of States have implemented these instruments through legal, policy and institutional frameworks, but further progress is needed in some developing countries, in particular the least developed countries.

The ocean absorbs around 23 per cent of annual CO2 emissions generated by human activity and helps mitigate the impacts of climate change. The ocean has also absorbed more than 90% of the excess heat in the climate system. Ocean heat is at record levels, causing widespread marine heatwaves, threatening its rich ecosystems and killing coral reefs around the world. Increasing levels of debris in the world’s oceans are also having a major environmental and economic impact. E very year, an estimated 5 to 12 million metric tonnes of plastic enters the ocean, costing roughly $13 billion per year – including clean-up costs and financial losses in fisheries and other industries. About 89% of plastic litter found on the ocean floor are single-use items like plastic bags. About 80% of all tourism takes place in coastal areas. The ocean-related tourism industry grows an estimated US$ 134 billion per year and in some countries, the industry already supports over a third of the labour force. Unless carefully managed, tourism can pose a major threat to the natural resources on which it depends, and to local culture and industry.

For open ocean and deep sea areas, sustainability can be achieved only through increased international cooperation to protect vulnerable habitats. Establishing comprehensive, effective and equitably managed systems of government-protected areas should be pursued to conserve biodiversity and ensure a sustainable future for the fishing industry. On a local level, we should make ocean-friendly choices when buying products or eating food derived from oceans and consume only what we need. Selecting certified products is a good place to start. We should eliminate plastic usage as much as possible and organize beach clean-ups. Most importantly, we can spread the message about how important marine life is and why we need to protect it.

Source:- www.un.org