Inequality within and among countries is a persistent cause for concern. Despite some positive signs toward reducing inequality in some dimensions, such as reducing relative income inequality in some countries and preferential trade status benefiting lower-income countries, inequality still persists.

COVID-19 has deepened existing inequalities, hitting the poorest and most vulnerable communities the hardest. It has put a spotlight on economic inequalities and fragile social safety nets that leave vulnerable communities to bear the brunt of the crisis. At the same time, social, political and economic inequalities have amplified the impacts of the pandemic.

On the economic front, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased global unemployment and dramatically slashed workers’ incomes.

COVID-19 also puts at risk the limited progress that has been made on gender equality and women’s rights over the past decades. Across every sphere, from health to the economy, security to social protection, the impacts of COVID-19 are exacerbated for women and girls simply by virtue of their sex.

Inequalities are also deepening for vulnerable populations in countries with weaker health systems and those facing existing humanitarian crises. Refugees and migrants, as well as indigenous peoples, older persons, people with disabilities and children are particularly at risk of being left behind. And hate speech targeting vulnerable groups is rising.

Facts and Figures:-

- Evidence from developing countries shows that children in the poorest 20 per cent of the populations are still up to three times more likely to die before their fifth birthday than children in the richest quintiles.

- Social protection has been significantly extended globally, yet persons with disabilities are up to five times more likely than average to incur catastrophic health expenditures.

- Despite overall declines in maternal mortality in most developing countries, women in rural areas are still up to three times more likely to die while giving birth than women living in urban centers.

- Up to 30 per cent of income inequality is due to inequality within households, including between women and men. Women are also more likely than men to live below 50 per cent of the median income

- Of the one billion population of persons with disabilities, 80per cent live in developing countries.

- One in ten children is a child with a disability.

- Only 28 per cent of persons with significant disabilities have access to disability benefits globally, and only 1per cent in low-income countries.

10.1 By 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average

10.2 By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status

10.3 Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard

10.4 Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality

10.5 Improve the regulation and monitoring of global financial markets and institutions and strengthen the implementation of such regulations

10.6 Ensure enhanced representation and voice for developing countries in decision-making in global international economic and financial institutions in order to deliver more effective, credible, accountable and legitimate institutions

10.7 Facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies

10.A Implement the principle of special and differential treatment for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, in accordance with World Trade Organization agreements

10.B Encourage official development assistance and financial flows, including foreign direct investment, to States where the need is greatest, in particular least developed countries, African countries, small island developing States and landlocked developing countries, in accordance with their national plans and programmes

10.C By 2030, reduce to less than 3 per cent the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 per cent

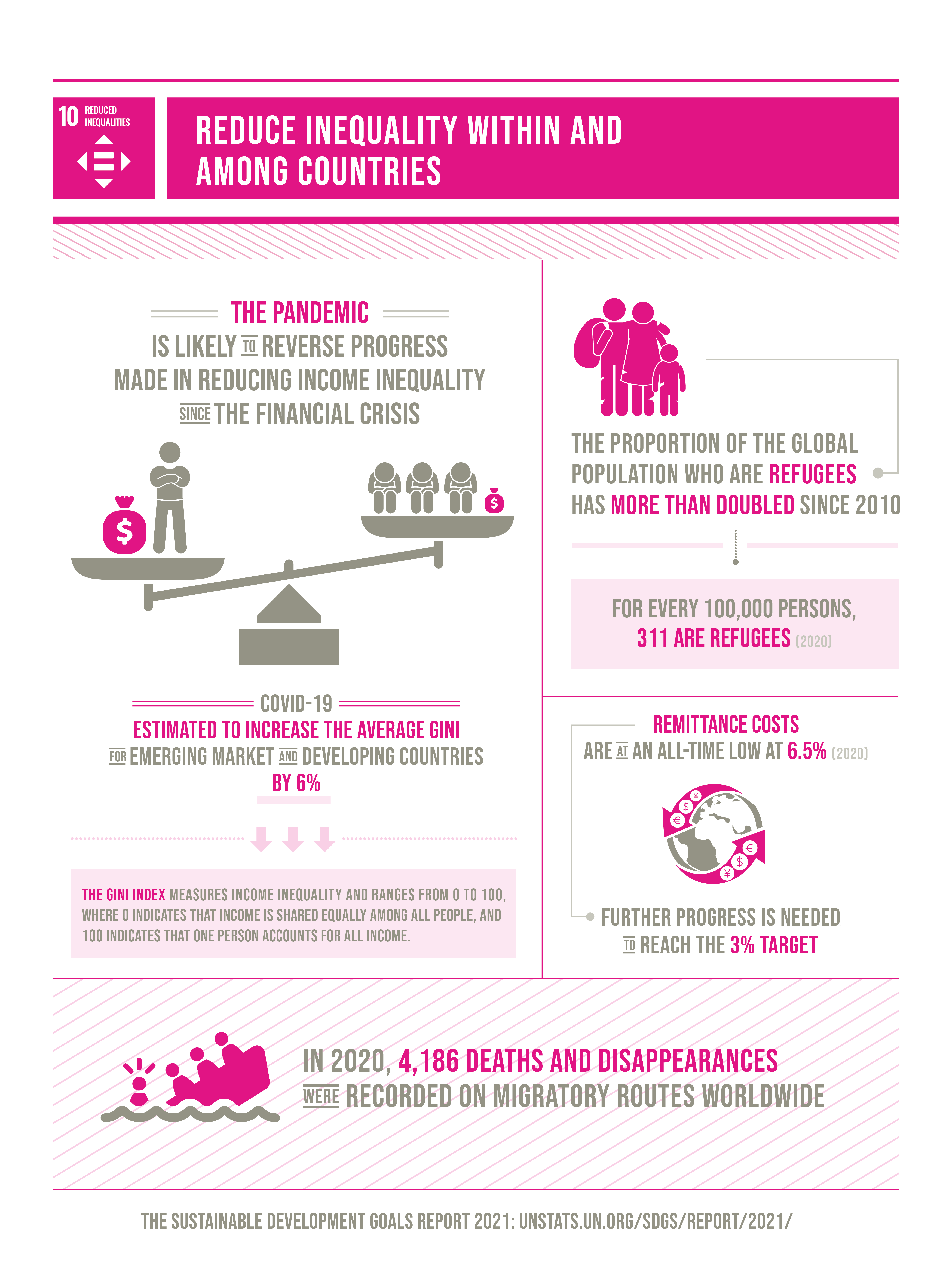

Before the pandemic, modest gains had been made in the reduction of inequality in certain areas, for example, reducing income inequality in some countries and territories, continuing preferential trade status for lower-income countries and territories and decreasing transaction costs for remittances. However, inequality persists, whether in relation to income, wealth, opportunity or other dimensions. The pandemic is exacerbating existing inequalities within and among countries and territories and hitting the most vulnerable people and the poorest countries and territories hardest, and is likely to delay the progress of the poorest countries and territories on the Goals by a full 10 years. Globally, the number of refugees reached its highest level on record in 2020. Even with strict COVID-19-related restrictions on mobility around the world, thousands of migrants died on their migratory journey.

According to estimates of the International Monetary Fund, the COVID-19 pandemic would increase the average Gini index for emerging market and developing economies by more than 6 per cent, with an even larger impact predicted for lowincome countries and territories.

Data from 44 countries and territories for the period 2014–2020 show that almost one in five people reported having personally experienced discrimination on at least one of the grounds prohibited under international human rights law. Moreover, women were more likely to be victims of discrimination than men. The health and socioeconomic situations of many groups already experiencing higher levels of discrimination have been further affected by the pandemic.

The data from 2019 on financial soundness indicators indicated some improvement of overall loan performance, while the levels of capital, which is the main buffer for absorbing losses, remained high despite a slight decline. The share of countries and territories reporting non-performing loans whose value exceeds 5 per cent of total loans declined from 41.9 per cent in 2018 to 39.5 per cent in 2019. Meanwhile, the share of countries and territories reporting a ratio of total regulatory capital to risk weighted assets of more than 15 per cent declined from 84.6 per cent in 2018 to 82.1 per cent in 2019, although the median rose from 17.9 per cent to 18.2 per cent over the same period.

In 2020, 4,186 deaths and disappearances were recorded along migratory routes worldwide, with an increase in fatalities on some routes. Despite the pandemic and mobility restrictions at borders across the world, tens of thousands of people continued to leave their homes and embark on dangerous journeys across deserts and seas.

By mid-2020, the number of people who had fled their countries and territories and become refugees owing to war, conflict, persecution, human rights violations and events seriously disturbing public order had grown to 24 million, the highest number on record. The number of refugees outside their country of origin has risen to 307 out of every 100,000 persons, more than double the figure at the end of 2010.

Globally, in 2019, 54 per cent of the 111 Governments with data reported having instituted a comprehensive set of policy measures to facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, which means that they have reported having policy measures in place for at least 80 per cent of the subcategories that make up the six policy domains of this indicator. The degree to which the policy measures were reported, however, varies widely across policy domains, with most countries and territories reporting measures for cooperation and partnerships and for safe, orderly and regular migration, and fewest countries and territories reporting measures for migrant rights and for socioeconomic well-being.

From 2017 to 2020, the proportion of products exported by the least developed countries and developing countries that receive duty-free treatment has remained unchanged at 66 and 52 per cent, respectively.

In 2019, total resource flows for development to developing countries from Development Assistance Committee donors, multilateral agencies and other key providers amounted to $400 billion, of which $164 billion was ODA.

The average global cost of sending a $200 remittance decreased from 9.3 per cent in 2011 to 6.5 per cent in 2020, bringing it closer to the international target of 5 per cent. The average annual decrease was 0.31 percentage points.

In today’s world, we are all interconnected. Problems and challenges like poverty, climate change, migration or economic crises are never just confined to one country or region. Even the richest countries still have communities living in abject poverty. The oldest democracies still wrestle with racism, homophobia and transphobia, and religious intolerance. Global inequality affects us all, no matter who we are or where we are from.

Reducing inequality requires transformative change. Greater efforts are needed to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, and invest more in health, education, social protection and decent jobs especially for young people, migrants and refugees and other vulnerable communities.Within countries, it is important to empower and promote inclusive social and economic growth. We can ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of income if we eliminate discriminatory laws, policies and practices. Among countries, we need to ensure that developing countries are better represented in decision-making on global issues so that solutions can be more effective, credible and accountable. Governments and other stakeholders can also promote safe, regular and responsible migration, including through planned and well-managed policies, for the millions of people who have left their homes seeking better lives due to war, discrimination, poverty, lack of opportunity and other drivers of migration.

Source:- www.un.org